Micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) technology enables the building of microoptical scanners that are well suited for low cost manufacturability and scalability as the MEMS processes emanate from the mature semiconductor microfabrication industry [

1]. For a long time, the potential of MEMS to steer or direct light has been well demonstrated in the field of free-space optical systems [

2]. In the 80s and early 90s, telecommunications became the market driver for the optical applications of MEMS, pushing the development of scanning micromirror systems for optical switches and network ports [

3]. More recently, many types of MEMS scanning mirrors have been developed, covering a wide range of applications from micrometer-scale array-type components to large scanners for high-resolution imaging [

4]. Thus, numerous optical imaging techniques such as confocal microscopy [

5,

6], multiphoton microscopy [

7,

8], and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [

9,

10,

11] have become important diagnostic tools in biomedicine, particularly offering a platform for endoscopic imaging. These MEMS scanners successfully replaced the bulky and high power consuming galvanometer scanners, providing compact, low cost, and low power consumption solutions for high speed beam steering. Further, 2D MEMS mirrors that scan in two axes are a pertinent alternative to the large galvano-scanners [

12].

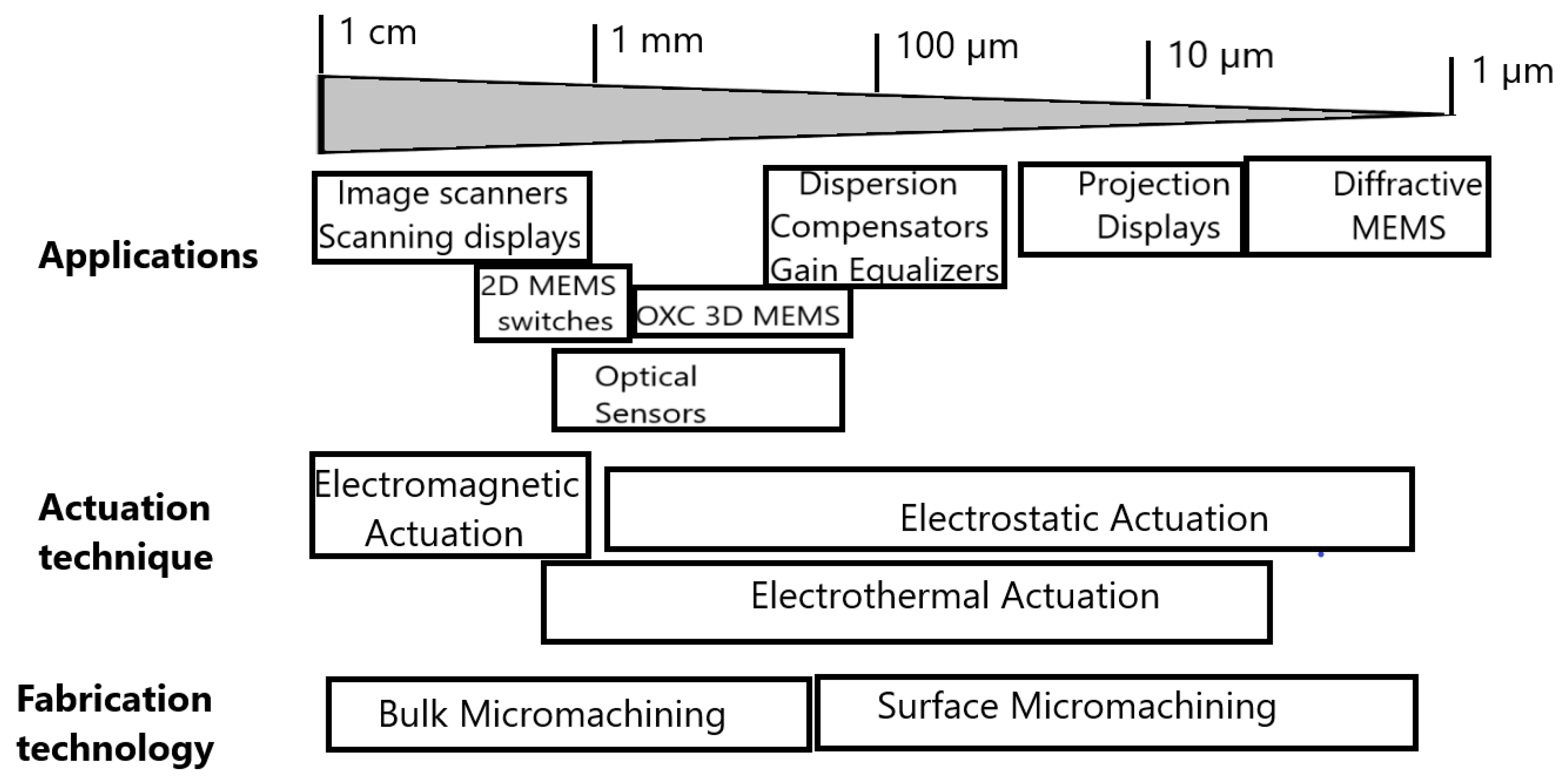

The MEMS scanner’s performances are closely linked to the size of the selected actuator, carrying the micromirror and the force developed by this actuator. represents a summary of scanning micromirror applications, including the corresponding actuation mechanisms and main microfabrication technologies [

13]. At the scale level, going from 1 mm to 1 cm, the MEMS technology combined with fiber optics enables miniature scanning components to be embedded inside the endoscopic imaging probes operating at high speed and high resonance frequency. The MEMS scanners are relatively easily integrated and adapted for low cost fabrication and low power consumption. The miniaturization performances and subsequent advances in standardized micromachining technologies have also offered numerous low cost and disposable OCT probes for the medical industry. Originally adopted by the ophthalmic community [

14,

15,

16], OCT has been used to image internal organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract [

17], and in the diagnosis of skin pathologies [

18,

19]. This strong interest for clinical applications pushed several companies to develop endoscopic OCT systems [

20]. Examples of commercial products are the clinical endoscope and catheter-based systems from the NvisionVLE

® Imaging System (South Jordan, Utah, USA) [

21], the intravascular OCT imaging systems from OPTIS™ (St. Jude Medical Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) [

22], Santec’s (Komaki, Japan) swept-source OCT systems [

23], Thorlabs (Newton, NJ, USA) OCT scanners [

24], as well as Mirrorcle (Richmond, CA, USA) microscanners [

25].

Figure 1. Applications, actuation mechanisms, and fabrication technologies for scanning micromirrors.

In this paper, we will demonstrate that for OCT imaging applications, the performance of the MEMS scanner is often limited by optics and intrinsic characteristics of actuation mechanisms. Here, optics require a small focused spot and dynamic focusing, imposing severe restrictions on scanning lens performances, while the actuation needs a high scanning speed, a low power consumption, a precise control of motion linearity, and reduced cross-axis coupling, which may distort the scanning patterns [

26,

27]. The group of OCT probes to be discussed in this paper do maintain such opto-mechanical performances, using different actuation mechanisms. Our wish is to demonstrate that the breakthrough of compactness is obtained when MEMS dual-axis beam-steering micromirrors [

28] are used to achieve scanning 3D OCT probes. In the case of endoscopic applications, they are small enough to be included into a standard endoscope channel, with an inner diameter of 2.8 mm. Further, 2D scanning motion can derive from electrostatic, electromagnetic, electrothermal, or piezoelectric actuation, providing the scanning mirrors for light beam steering, operating at high speed and fully controlled by non-resonant or resonant regimes. However, we intentionally excluded from the present study piezoelectric actuation and we consider only the three other actuation mechanisms for MEMS scanning mirrors that are the most widely used in OCT applications.

2. Requirements for MEMS Microscanners

From the user point of view, performances of scanning micromirrors are defined by the maximum scan angle, the number of resolvable spots which represents the scan resolution, the resonance frequency, as well as the surface quality vs. the smoothness and flatness of micromirrors.

The number of resolvable spots

N of a scanning mirror is defined as a function of optical scan angle

θopt and beam divergence

δθ, as shown in :

where

D is the mirror diameter,

a represents the aperture shape factor (

a = 1 in the case of a square aperture and 1.22 for a circular aperture) and

λ is the illumination wavelength.